Where Three Dreams Cross, Whitechapel Gallery, London

A century and half of photographs from the subcontinent wrong-foots Kipling and the post-colonial blow-hards

Thirty years ago, the critic Edward Said set the cat among the pigeons by publishing Orientalism, a work which put forward the alarming suggestion that the East is a figment of the West’s imagination.

Only by seeing a culture as other, can you control it: Kipling, Delacroix and Flaubert, Orientalists all, helped to create an idea of the East which in turn allowed it to be overrun by the West.

That Said’s thinking still gives us gyp is shown by the dominance today of what is known, annoyingly, as “post-colonial discourse”, a category that includes the shows I’ll be reviewing both this week and next.

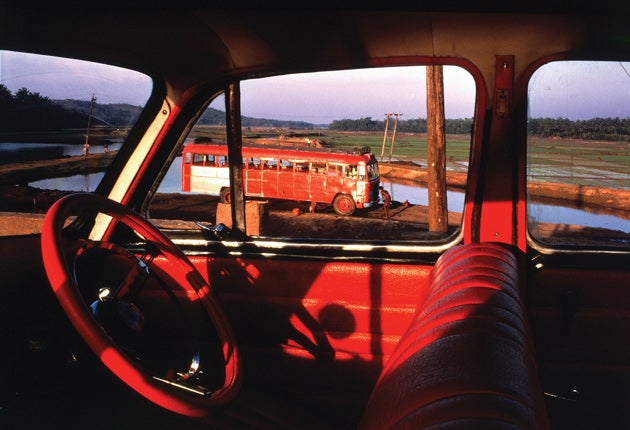

If one medium was going to lend itself to cultural imperialism, then photography is arguably it. It was, after all, a Western invention, and the rise of the camera coincided neatly with that of European colonialism. Nothing conveyed the otherness of the East more vividly than a sepia photograph of barefoot girls in bangles, or rajahs shooting tigers from a howdah. So a show at the Whitechapel Art Gallery called Where Three Dreams Cross – a selection of 150 years of photographs from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh – would seem particularly prone to post-colonial interpretation. It is a mark of the exhibition’s cleverness that it isn’t, particularly – that the East’s counter-colonial imagining of the West is only one of the many currents eddying about these images, and not the most important one at that.

In part, this is down to the show’s thematic structure. Images are divided into Portrait, Performance, Family, Streets and Body Politic. Had Three Dreams’ curators hung the work chronologically and country-by-country, it would have felt like a display in an ethnographic museum. Like Mrs Moore in EM Forster’s Marabar Caves, the show would also have imposed a Western rationale on something better seen dharmically, with a taste for happy connection.

In the great boum of Performance, for example, are Bollywood images of the 1940s and 1950s that show a clear eye to Western movie magazines. But the most American of these turn out not to be Bollywood at all. The Bette Davis lookalike who smokes broodily to camera is the contemporary Bangalore-based artist, Pushpamala N, and her self-portraits, made a couple of years ago, play a quiet game of history.

This has to do with the artist's anticipation of who her images will be seen by, and whether local and Western audiences – her work has been bought by Charles Saatchi – will bring the same cultural expectations to them.

Across the way are other photographs taken, I would think, in the 1890s and featuring fakhirs standing in what looks like a bedroom at the Ritz: one, naked but for a loincloth and sporting a titanic white beard, poses in front of a belle époque fireplace. It would be easy to imagine that this image was made by a member of the British Raj with a taste for the exotic, although all the photographs in this show were actually taken by natives of the three countries involved.

At the heart of Where Three Dreams Cross, in other words, lies the unsettling question of who, culturally speaking, is looking at whom. That Kipling was wrong about East being East and West West is amply proven by a suite of six contemporary portraits of Eurasians, the mixed-race relics of a one-time British Empire. One, a woman in late middle-age, wears the navy suit and fake-Hermès scarf you might see in Weston-super-Mare. Even her door looks north-Somerset. What can an Indian photographer have made of it, and of her? What do we? Around the White-chapel Gallery live 70,000 Bangladeshis who are likewise part of the untidiness of Britain's colonial history. How (or whether) they will see the work in this show is a question that hangs in the air.

As I said, though, the real triumph of Where Three Dreams Cross is that it manages to avoid the grimmer backwaters of post-colonial discourse. What prevails is the image – photojournalistic, social-realist, studio-made, hand-tinted, and at times just plain bonkers. Unfortunately, the Saatchi Gallery's matching show of contemporary Indian art, The Empire Strikes Back, wasn't hung in time for me to review this week, although a browse through the catalogue suggests that it, too, is more of a celebration than a historical diatribe. You'll see Pushpamala N's photographs there, too, which is reason enough to go.

To 11 April ((020-7522 7888)

Next Week:

Charles Darwent continues the post-colonial theme by seeing Chris Ofili's show at Tate Modern and Afro Modern at Tate Liverpool

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies